Summary

Some of the problems we face online, like privacy, control, and access to data are solved when we consider decentralized approaches. This blog post discusses several benefits of decentralized design and modeling.

In Programming the Cloud With Persistent Data Objects I describe a programming model that is supported by KRL that gives rise to what I've called at various times "personal clouds" or "persistent data objects" (PDOs). PDOs support a decentralized programming model that gives people, places, organizations, and things their own cloud capable of storing data and running programs. Because these clouds are cheap to create and maintain, we can support billions, even trillions of them.

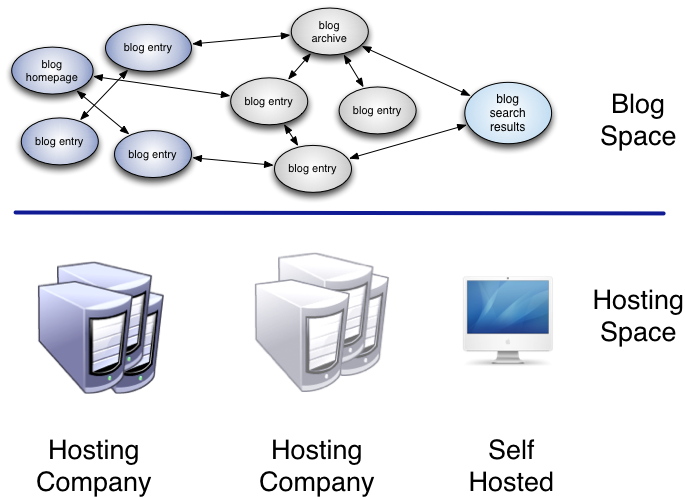

This decentralized programming model spreads the data and computation out. As I described in Building a Blog with Personal Clouds, a single blog might be supported on multiple machines hosted by different companies and yet appear to visitors as if it were a single, self-consistent entity. Here's a picture of the decentralized blog:

This picture nicely illustrates the difference between a blogging platform running on a set of distributed servers and a truely decentralized blogging system. The distributed blogging system might run on multiple machines, but they would all be within the authority of a single entity. Google runs thousands of servers, but they all belong to Google. In a decentralized system, the authority might be—will likely be—spread out.

This is more complicated than simply building a single blog platform running on a standard distributed model, so why do it? I'm very keen on decentralized programming models and PDOs for several reasons that I'll lay out in the following sections.

PDOs Support Structural Privacy By Design

Decentralized models nicely support what has been called privacy by design. Decentralized systems can provide privacy and user control structurally rather than by agreement. Let's explore this.

The personal computer provides a perfect model of how structural privacy by design works. If you use TurboTax to prepare your taxes on your laptop:

- The data is on your laptop and you understand very clearly where it is.

- The data isn't shared until you share it.

- If the program tries to share data under the covers, systems running for you and under your control could detect the data transfer. Consequently there is a decentralized construct that allows auditing the performance of the program.

- If you still have the program and the data years from now, you'll likely be able to run it and get some value. TurboTax's status (up or down) doesn't have any bearing on this.

In short, the user understands the data model and feels comfortable in how the data is being used and shared.

If, on the other hand, you prepare your taxes at the TurboTax web site:

- The data is "in the cloud" and you don't know what's being done with it. The good news is that they're managing it. The bad news is you can't.

- You're trusting TurboTax and their assurances that the data is protected.

- Only an invasive audit of TurboTax servers will convince you that they are doing what they say they'll do.

- If Intuit decides to shut down the TurboTax Web site, you're screwed.

Structural privacy and control is preferable, where possible, to agreement-based privacy and control. The CloudOS at the foundations of PDOs is designed to provide such structural privacy and control:

- Programs run in your space under your control, even though they might be from a third party.

- The data remains under your control and isn't shared until you want.

- Programs that nefariously share data can be audited and detected by programs run by you in your cloud.

- The programs are yours regardless of their maker's status.

People are working on agreement models that are more granular, better specified, and more trusted than current terms of service, but I don't think we ought to rely on agreements when we can have structure. Agreements are for situations where structure cannot be used. They shouldn't be the default or the last line of defense.

PDOs Provide a "Locus of Control:" No More Silos

I use Endomondo to track my bike rides. I used to have a Fitbit until it went through the washer. I also have Withings scale and blood pressure cuff. These companies provided me with connected hardware and Web sites that can be described as "data silos."

Combining my Fitbit and Endomondo data is hard. Partly that's a semantic problem and partly it's because data from both companies resides in the respective company's Web apps and APIs until they create a relationship. Now, it turns out that Fitbit and Endomondo have created such a relationship, but am I to be held hostage to the bizdev bandwidth of every company that creates a connected device to be able to hook them together?

Move over, they will all want to have an application for my mobile device. The more connected things I get the more untenable this solution seems. I've probably got a dozen applications for connected devices. What happens when I have hundreds? The current model doesn't scale.

My personal cloud can serve as the meet point for these various connected devices and the data they produce. This is not to say that all the data will need to be stored in my personal cloud. It may very well continue to live on at various servers. But my personal cloud will be the place where all my data is accessible. Ideally, rather than merely proxying the APIs of various companies, my personal cloud will provide standardized access to specific kinds of data so that an application using my API needn't be bothered with whether I use Endomondo or Runkeeper.

This is a tall order, but I think that this is precisely where semantic technologies like XDI will play a role in mapping proprietary APIs to my API. There's still much to do to make this reality, but there are also powerful incentives.

Eventually, I'd like companies to provide me with the option of storing my data in my cloud in storage that I own and control. This is all doable. My cloud would give me options about the storage providers I use (i.e. Dropbox, Box.com, Amazon, etc.) and Flickr, TurboTax, and other apps would store my data in my space rather than theirs.

PDOs Adapt to Match Real-World Circumstances

I had an exchange with a friend about personal data and modeling real-world situations. The discussion follows the TurboTax theme from above.

[I]f my wife and I want to have a financial app that helps file our taxes, does the app run in my cloud or my wife's?

In practice, we want the user experience to give the impression that we both have shared access to the same tax filing app that magically consolidates our data. While this could be achieved with the same app running in both clouds and syncing data (a very nontrivial task), the model breaks down as soon as the app developer wants to do something more sophisticated like importing my past TurboTax records.

Interestingly, this is as much a modeling problem as anything and decentralized systems of PDOs provide a nice way to represent that model. A husband and wife filing taxes jointly is a different entity than either the husband or the wife. So, it needs a PDO to represent it. That PDO would have connections to and permissioned, fine-grained access to data in both the husband's personal cloud (PDO) and the wife's personal cloud. This PDO could run the tax applications, manage imports and exports, connect to APIs related to the joint entity's business, and so on.

What's more, this PDO represents the joint husband-and-wife entity for whatever period that entity exists. So, if a divorce occurs, the PDO can continue to exist, hold data about it's historical interactions, and continue to respond to permissioned requests relevant to the joint entity's business. Both the husband and wife would continue to have access to it. We don't need a Web site to model that. A decentralized approach works as well. Better in many cases.

Conclusion

PDOs are more than personal data stores. A "store" or "locker" connotes static data waiting for someone to come along and do something. PDOs are more than that. They are agents. They act. The respond to stimulus (in the form of events) and take action. A "store" or "locker" also suggests centralization, although that needn't be the case. As we've seen, PDOs give rise to decentralized networks of interacting agents. Each might have a chunk of data, but that's not what defines them.

I think decentralized models based on the idea of persistent data objects holds significant promise. As more and more things that I care about get connected, the only hope for building consistent models of those things and how they relate to me, my family, work, and so on is to view them as stand-along virtual representations of the thing they model. I'm excited by the possibilities.