Cross-Domain Delegation in a Society of Agents

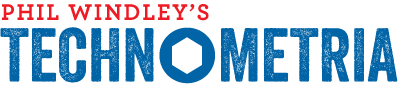

In the previous post, I explored how a primary agent can safely delegate work to subagents within a single system. The key idea was that delegation should be modeled as data and evaluated by policy. When the subagent acts, the policy engine evaluates the request together with the delegation record, confining the authority the subagent can exercise.

That architecture works because all of the actors operate within the same domain of control. The system that issues the delegation also controls the policy decision point that enforces it. Delegation becomes deterministic: authority is granted, scoped, and enforced by policy.

Cross-domain delegation is different. When an agent delegates authority to another agent in a different system, the delegating system no longer controls the enforcement point. The receiving agent may have its own policies, incentives, and interpretation of what the delegation means. Authority is no longer confined by a single policy engine.

This means cross-domain delegation cannot be solved purely as a technical mechanism between two agents. Instead, it must be understood as a property of the ecosystem in which those agents operate. For delegation across domains to work reliably, the agents must participate in a shared environment that provides norms, expectations, and enforcement mechanisms.

In other words, cross-domain delegation only works inside what we might call a society of agents.

Within such a society, three mechanisms work together to make delegation meaningful. First, policies create hard boundaries that deterministically constrain what an agent can do within its own domain. Second, promises allow agents to communicate intent and coordinate behavior across domains. Third, reputation provides a form of social memory, allowing each participant to evaluate whether other agents have honored their commitments in the past.

None of these mechanisms alone is sufficient. Policies without promises cannot coordinate behavior across systems. Promises without enforcement are merely declarations of intent. Reputation without boundaries turns governance into little more than hindsight.

But together they provide the foundation for a society in which agents can safely exchange authority.

Foundations of a Society of Agents

For agents to delegate authority across domains reliably, they must operate within a broader social structure. Just as human societies rely on norms, commitments, and collective memory to sustain cooperation, a society of agents depends on three complementary mechanisms: policies, promises, and reputation1. Together, these three mechanisms create the structural foundation for cross-domain delegation.

Policies define the boundaries within which an agent can operate. These boundaries are enforced deterministically within each agent's own domain through policy evaluation. Policies constrain what an agent is capable of doing, regardless of its intentions or the requests it receives.

Within those boundaries, agents make promises. A promise communicates how an agent intends to behave, but those promises are credible only when they are grounded in the agent's own policies. In practice, promises should be derived from the agent's policy set, since those policies determine what the agent is allowed to do. In the context of delegation, promises might describe the scope of actions an agent will take, the resources it will access, or the limits it will observe. Promises allow agents in different domains to coordinate their behavior and form expectations about how delegated authority will be used.

The promise is a signed, structured statement of how Agent B will enforce spend limits if delegated, including the policy semantics, required inputs, and audit signals—without referencing any specific credential. A promise might look like the following JSON:

{

"type": "agent.promise.v1",

"issuer": "AgentB",

"audience": "AgentA",

"promise": {

"capability_class": "purchase.compute",

"intent": "I will operate within any delegated spending limit.",

"policy_commitment": {

"rule": "deny_if_total_spend_exceeds_limit",

"required_context": [

"spending_limit.max_spend",

"spending_limit.currency",

"spending_limit.expires",

"purchase.amount",

"purchase.currency",

"spend.total_to_date"

],

"enforcement_point": "AgentB.PDP"

}

},

"signature": "..."

}

Note that the policy commitment is explicit, allowing the delegating agent to structure the delegation in a way that the receiving agent's policies can enforce.

Reputation provides the system's social memory. After agents interact, each participant records the observed outcomes of those interactions and uses that information to guide future decisions. Importantly, reputation in a society of agents is not centralized. Each agent maintains its own memory of past interactions and evaluates other agents based on its own experiences and observations.

Policies constrain behavior, promises communicate intent within those constraints, and reputation records whether those promises are honored. None of these mechanisms alone is sufficient. Policies without promises cannot coordinate behavior across domains. Promises without enforcement are merely declarations of intent. Reputation without boundaries turns governance into little more than hindsight. Taken together, however, they form the institutional structure of a society of agents: an ecosystem in which autonomous systems can confidently exchange authority across domain boundaries.

Why Promises Alone Are Not Enough

Promise theory offers a useful way to think about cooperation between autonomous systems. As Volodymyr Pavlyshyn explains, the behavior of distributed systems can be understood as emerging from "voluntary promises made and kept by independent, autonomous agents." In promise-based models, agents declare the behavior they intend to follow and other agents decide whether to rely on those declarations. This approach emphasizes voluntary cooperation rather than centralized control, making it attractive for distributed systems composed of independently operated components.

This perspective captures an important truth about distributed systems: autonomous agents cannot be forced to behave by outsiders. They can only promise how they intend to behave. In a society of agents, promises play an essential role because they allow agents to communicate intent across domain boundaries. When one agent delegates authority to another, it must understand how that authority will be used. A promise can express that understanding. For example, a promise might encode that an agent intends to restrict its actions to a particular purpose, stay within a spending limit, or operate only within a defined scope.

However, promises alone are not sufficient to govern delegated authority. A promise is not a mechanism of enforcement. An agent may sincerely intend to honor a promise and still violate it due to error, misconfiguration, or unforeseen circumstances. Alternatively, an agent may deliberately break a promise in pursuit of it's goals. In a system governed only by promises, the primary consequence of a violation is reputational: the offending agent may lose trust and future opportunities for cooperation.

But for many forms of cross-domain delegation, that is not enough. Delegated authority often enables consequential, real-world actions like spending money, accessing data, provisioning infrastructure, or controlling physical devices. In these contexts, relying solely on promises would mean trusting that the receiving agent will behave correctly without any deterministic guardrails. This is where policy boundaries become essential. Policies constrain what an agent is capable of doing within its own domain, meaning delegated authority cannot exceed predefined limits.

Reputation closes the loop. By observing outcomes and recording them as part of its social memory, an agent can evaluate whether another agent consistently honors its promises and operates within agreed boundaries. Over time, this reputation influences whether future delegations are granted and under what conditions.

Together, these mechanisms transform promises from mere declarations into meaningful commitments. Policies establish the boundaries within which promises must operate, and reputation records whether those promises are kept. Only within such a structure can a society of agents support reliable cross-domain delegation.

In the next section, we'll look at how these mechanisms work together during an actual delegation interaction between two agents operating in different domains.

How Cross-Domain Delegation Works

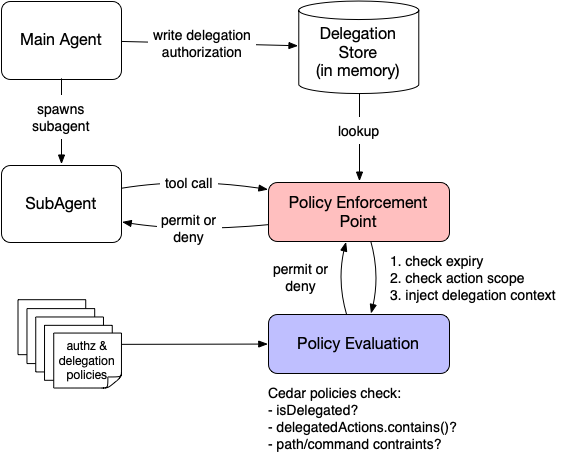

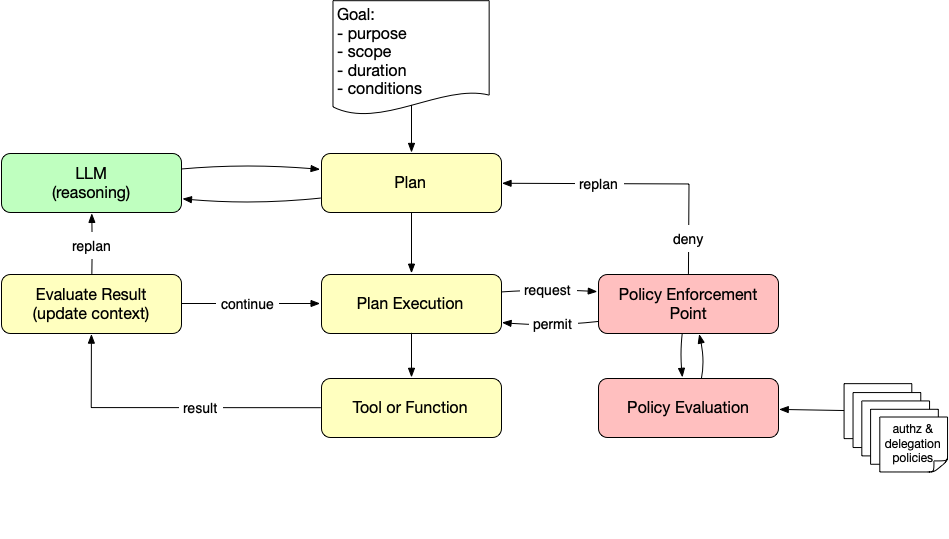

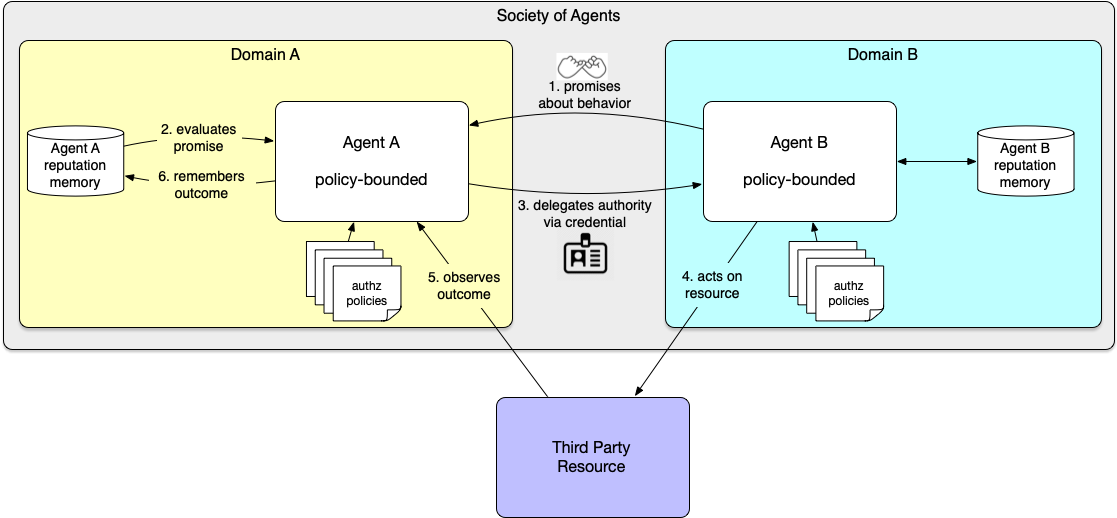

Cross-domain delegation becomes easier to understand when we look at the interaction between two agents operating in different domains. The following diagram illustrates the interactions between two agents. Agent A is delegating a task to Agent B.

When an agent needs another agent in a different domain to perform an action—such as purchasing a product or provisioning compute resources—it must decide whether to delegate authority. Agent A begins by identifying Agent B as a potential delegate. Because Agent B operates under its own policies and control, Agent A cannot directly inspect or enforce those policies. Instead, Agent B describes how it intends to behave when exercising delegated authority, expressing commitments derived from its own policy boundaries. Agent A then evaluates those commitments before deciding whether to delegate. The interaction unfolds as follows.

- Agent B promises bounded behavior—Before any authority is delegated, the receiving agent communicates its intended behavior. In promise-theory terms, Agent B declares how it intends to use the delegated capability. For example, it might promise to stay within a defined spending limit, operate only on a specific resource, or perform a narrowly scoped task.

- Agent A evaluates the promise—This evaluation is informed by Agent A's social memory, a record of past interactions with other agents in the ecosystem, including Agent B. If previous interactions suggest that Agent B consistently honors similar commitments, the promise may be considered credible.

- Agent A delegates authority via a credential—If the promise is accepted, Agent A grants authority using a credential that represents the delegated capability. This credential might be a token, a signed assertion, or a verifiable credential describing the scope and limits of the delegation.

- Agent B acts on the resource—Agent B uses the credential to perform the delegated action on a third-party resource. The credential provides context to Agent B’s policies so they can constrain what it is permitted to do on Agent A’s behalf. It may also be presented to the third party as evidence that Agent B is acting under authority delegated by Agent A.

- Agent A observes the outcome—Agent A observes the effects of the action, using either signals produced by the system in which the action occurred or evidence such as a cryptographic receipt.

- Agent A updates its reputation memory—Finally, Agent A records the outcome in its social memory. This updated reputation influences how Agent A evaluates future promises from Agent B.

This sequence illustrates how policies, promises, and reputation work together. Policies enforce deterministic boundaries within each agent's domain. Promises communicate intent across domains. Reputation records whether those promises are honored. Together, these mechanisms allow independent agents to exchange authority while preserving their autonomy.

Why Delegation Requires a Society

The interaction described above may appear straightforward, but it only works reliably when agents operate within a broader ecosystem that supports these mechanisms through legal agreements, protocols, and code . Without such an environment, cross-domain delegation quickly becomes fragile. Consider what happens if any of the three elements are missing.

If policies are absent or poorly defined, delegation becomes dangerous. Even if an agent intends to behave responsibly, there are no deterministic boundaries constraining what it can actually do. A misconfiguration, software bug, or malicious action could easily exceed the intended scope of authority.

If promises are absent, agents cannot coordinate their behavior across domains. Delegation would become little more than the transfer of a credential with no shared understanding of how that authority should be used. Agents would have no way to express intent or set expectations about future behavior.

If reputation is absent, agents have no memory of past interactions. Each delegation decision would have to be made in isolation, without any information about whether the receiving agent has honored similar commitments in the past.

A society of agents solves these problems by providing the structural conditions that allow these mechanisms to reinforce one another. Policies establish the norms and boundaries within which agents operate. Promises allow agents to communicate intentions within those norms. Reputation provides the social memory that allows trust to evolve over time.

Importantly, this social memory is not centralized. Each agent maintains its own record of interactions and forms its own judgments about the behavior of others. Two agents may therefore reach different conclusions about the same participant depending on their experiences. Trust emerges not from a single global authority but from the accumulation of many local observations.

Within such a society, cross-domain delegation becomes sustainable. Agents can exchange authority while maintaining autonomy, and trust develops gradually through repeated interactions.

Credentials as Delegated Authority

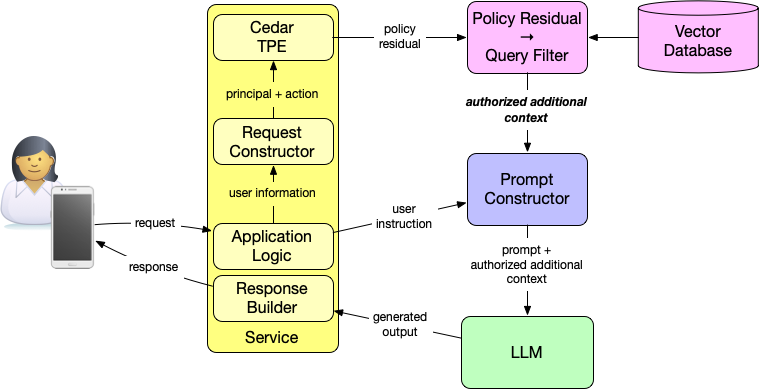

In the interaction described earlier, Agent A grants authority to Agent B using a credential2. This credential is the artifact that represents the delegation. It encodes the capability being granted together with the limits under which that capability may be exercised.

Conceptually, the credential functions as a portable representation of authority. Instead of granting direct control over a resource, the delegating agent issues a signed statement describing what the receiving agent is allowed to do. The receiving agent can then present that credential when acting on the delegated authority.

For example, a credential might express a delegation such as:

Agent A authorizes Agent B to spend up to $500 to procure compute resources before midnight.

One way to represent that delegation is with a signed credential that encodes the capability and its constraints, such as the following:

{

"issuer": "AgentA",

"subject": "AgentB",

"capability": "purchase.compute",

"constraints": {

"max_spend": 500,

"expires": "2026-03-05T23:59:59Z",

"purpose": "procure temporary compute capacity"

},

"signature": "..."

}

When Agent B attempts to exercise the delegated authority, the credential serves two roles. First, it provides contextual inputs to Agent B’s policy engine, allowing its policies to determine whether the requested action falls within the delegated limits. Second, the credential may be presented to the receiving system as evidence that Agent B is acting under authority delegated by Agent A. The credential expresses the delegation, while policy enforcement determines whether the requested action is permitted in the current context.

This separation is important. Credentials carry the delegated authority and provide evidence of that delegation, but they do not enforce it. Enforcement occurs through policy evaluation in the systems where the action takes place. In this way, credentials serve as the mechanism by which authority moves between domains, while policies remain the mechanism that constrains how that authority can be used.

Trust Emerges from Interaction

The sequence described above is not a one-time mechanism but an ongoing pattern of interaction. Each delegation becomes an opportunity for agents to learn about one another.

Agent A evaluates Agent B’s promise, decides whether to delegate authority, and observes the outcome of the resulting action. That outcome becomes part of Agent A’s social memory. If Agent B consistently operates within the bounds it promises, future delegations may become easier or broader. If it violates those expectations, Agent A may decline future delegations or restrict the scope of authority it is willing to grant.

Over time, these repeated interactions shape how agents evaluate one another. Trust is built gradually through experience.

Importantly, reputation is not centralized. Each agent maintains its own social memory and evaluates others based on its own observations. Two agents may therefore reach different conclusions about the same participant depending on their experiences. Trust emerges from the accumulation of many independent judgments rather than from a single global score.

Within such a system, cross-domain delegation becomes sustainable. Policies constrain what agents can do, promises communicate how they intend to behave, and reputation captures whether those expectations were met. Delegation decisions can therefore evolve over time as agents learn from the outcomes of their interactions.

Toward Agent Societies

As autonomous systems become more capable, the need for reliable cross-domain delegation will only increase. Agents will increasingly interact with services they do not control, operate across organizational boundaries, and act on behalf of people and institutions in environments that no single system controls.

As we've seen, traditional approaches to authorization are not sufficient in these settings. A single policy engine cannot govern the entire ecosystem, and centralized trust authorities cannot anticipate every interaction. Instead, the systems that participate in these environments must be able to coordinate their behavior while preserving their independence. A society of agents provides the framework for doing so.

Within such a society, policies define the boundaries that constrain behavior within each domain. Promises allow agents to communicate intent and establish expectations about how delegated authority will be used. Credentials carry that authority across domain boundaries in a portable form. Reputation provides the social memory that allows trust to develop through repeated interaction.

These mechanisms together create the conditions under which independent systems can cooperate safely. Authority can be delegated without surrendering control, and trust can evolve through experience rather than requiring universal agreement in advance.

Importantly, this vision does not depend on a single global infrastructure for trust. Each agent maintains its own policies, evaluates promises according to its own criteria, and records its own social memory of past interactions. Trust emerges from the accumulation of many local judgments rather than from a centralized reputation system.

In this sense, the ecosystems we build for autonomous agents should resemble the social systems that humans have relied on for centuries. Cooperation depends not on perfect foresight or universal control, but on a combination of rules, commitments, and shared memory.

Cross-domain delegation is therefore not simply a technical challenge. It is a problem of institutional design. Building reliable agent ecosystems requires creating the social structures that allow autonomous participants to cooperate while remaining independent.

⸻

Notes

- This perspective reflects a long arc in my thinking about distributed trust systems. In earlier work on online reputation systems, I argued that reputation emerges from the accumulation of interactions recorded by participants rather than from a single global score. Later, in writing about societies of things and promise-based systems, I explored how autonomous devices might cooperate through voluntary commitments rather than centralized control. More recently, the development of verifiable credentials and decentralized identity systems has provided practical mechanisms for representing authority and claims as portable artifacts. The ideas in this article bring these threads together: trust in distributed ecosystems emerges not from a central authority, but from the interaction of policies, promises, credentials, and reputation over time.

- Delegated authority can also be represented using capability tokens, a long-standing concept in distributed systems and operating system design. Capability systems encode authority directly in tokens that grant access to specific resources or operations. Whether expressed as credentials or capability tokens, the underlying idea is the same: authority is represented as a transferable artifact that can be presented when performing an action.

- This architecture does not eliminate the possibility of fraud or intentional deception. An agent might still violate its promises, misuse delegated authority, or misrepresent its capabilities. What the mechanisms described here provide is not perfect prevention but structured risk management: policies constrain what actions are technically possible, promises clarify expected behavior, and reputation allows participants to learn from past interactions. The result is a system that reduces accidental or careless misuse of authority while allowing the ecosystem to adapt to bad actors over time.

Photo Credit: Agents making promises and exchanging credentials from ChatGPT (public domain)